NEWS

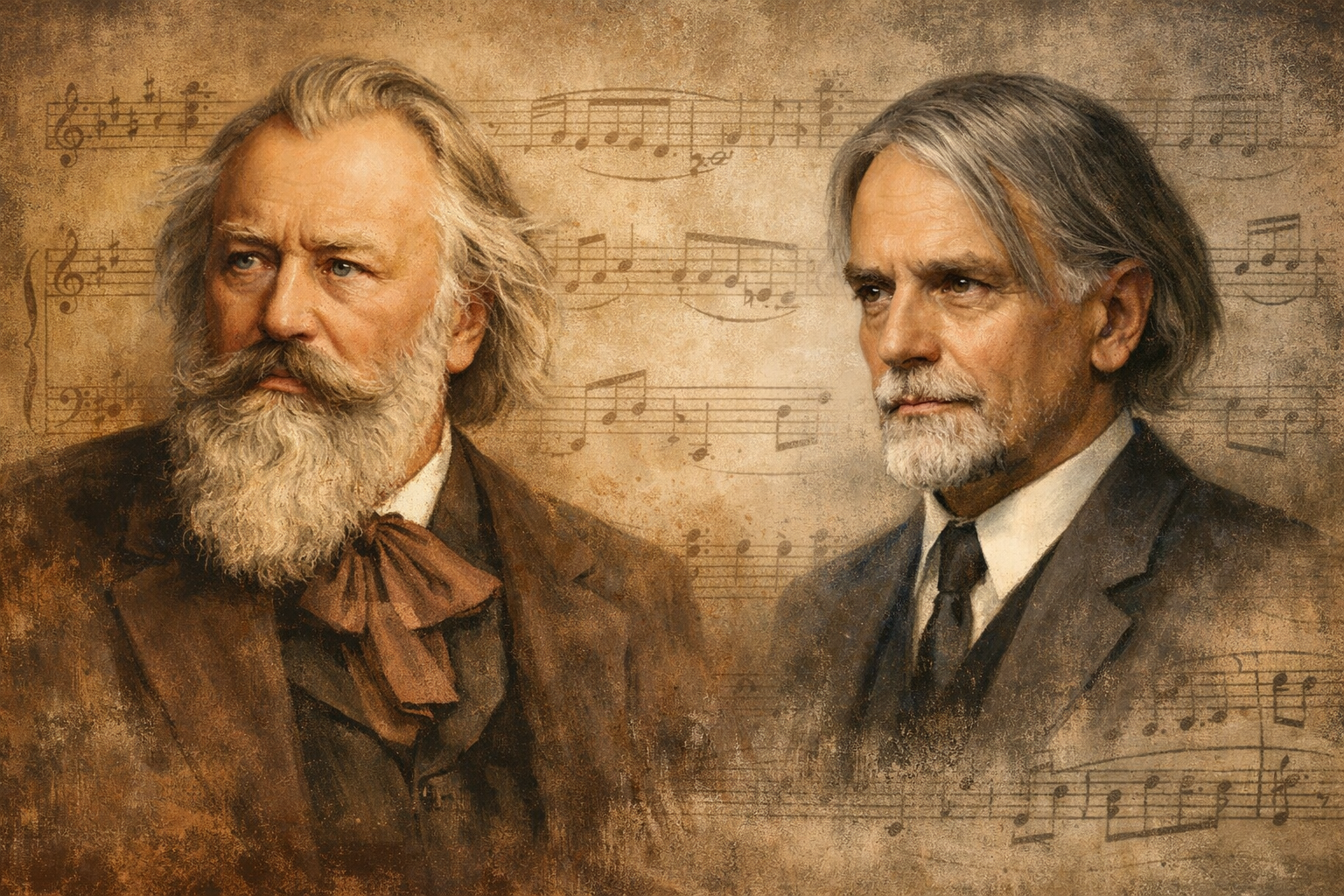

Preview: ‘Brahms, Kodály take center stage with Tulsa Symphony Orchestra’

TULSA – The Claremore Daily Progress has published a preview of Brett Mitchell’s upcoming subscription program with the Tulsa Symphony Orchestra:

The Tulsa Symphony Orchestra will open the new year at 7:30 p.m. Saturday at the Tulsa Performing Arts Center.

Much-in-demand guest conductor Brett Mitchell leads the performance, bringing his broad orchestral experience and distinctive musical insight to the Tulsa stage.

The evening opens with the Brahms favorite "Variations on a Theme" by Haydn, followed by Kodály’s lively "Dances of Galánta," inspired by Hungarian folk tunes and known for its bold rhythms. The evening’s finale showcases Brahms’s radiant "Symphony No. 2 in D major," a piece celebrated for its warmth and melodic beauty.

Brett Mitchell brings a wealth of experience to the performance, having led major orchestras at home and abroad including the Cleveland Orchestra, Houston Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic and New Zealand Symphony Orchestra. Known for his engaging presence and thoughtful interpretations, Mitchell returns to the Tulsa stage to interpret an engaging program highlighting the artistry and influence of Brahms and Kodály.

“This program brings together two masters of orchestral imagination and structure,” said Ron Predl, executive director of the Tulsa Symphony Orchestra. “From the elegance of Brahms to the rhythmic vitality of Kodály, audiences can expect an entertaining and moving symphonic experience led by this world-class conductor.”

To read the complete preview, please click here (paywall).

Feature: ‘Simply a Composer’s Advocate’

Photo by Roger Mastroianni

The American technical formal apparel company Coregami has announced Brett Mitchell as a brand ambassador, and journalist Owen Clarke has marked the new partnership with a 2,000-word feature article about the multifaceted conductor, composer, and pianist.

Simply a Composer’s Advocate

In a profession often defined by tradition and the worship of past masters, conductor and Coregami ambassador Brett Mitchell has a strict rule: never copy the giants.

“I would rather be a first-rate Brett Mitchell than a second-rate Leonard Bernstein,” he told me. “I want everything that I do, for better or worse, to come genuinely from me. That's the only way it'll be new.”

Born and raised in Seattle, Washington, Mitchell was the oldest of three boys. No one else in his family was a musician, and he wasn’t introduced to classical music until high school. As a kid, he was surrounded by the pop artists of his parents’ generation, like the Beatles, Simon and Garfunkel, Billy Joel, and Elton John. As he grew into his teens, in the early 1990s, his influences changed. “There was no way to escape grunge in Seattle at that time,” he joked. “If you go look at my 8th grade yearbook, our jazz band photo, we’re all in flannels and ripped jeans,” he said. “Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, those bands were huge for me back then.”

As he entered high school, however, he became more interested in classical music. In particular, he loved the soundtracks of popular films at the time, movies like Superman, Indiana Jones, E.T., and Star Wars—all scored by John Williams. “I wouldn’t have had a career if it weren’t for falling in love with John’s music,” Mitchell said.

Mitchell knew he loved music, but he wasn’t sure how he wanted to approach it. For a time he thought he might want to be a pianist, or perhaps a film composer. So he started writing bigger and bigger pieces, and his high school band director eventually said, “Why don’t you conduct this piece that you wrote?”

And in October of 1995, exactly thirty years ago, a 16-year-old Mitchell conducted his first piece of music. “Was I terrified? Yes, absolutely,” he said, laughing. “But it was that night in October ‘95 that I really decided, ‘Okay, I think this is the direction I want to go in life.’” After high school, he earned an undergraduate degree in music composition from Western Washington University, and then a master’s and doctorate in orchestral conducting from the University of Texas. By age 26, Mitchell was teaching at Northern Illinois University, and later that same year, he landed his first professional job as an assistant conductor for Orchestre National de France in Paris. From there, he was off to the races.

(Readers can read Mitchell’s full biography on his website. Currently, he is the music director of the Pasadena Symphony, and the artistic director and conductor for Oregon’s Sunriver Music Festival. Just two weeks ago, he was named piano company Steinway & Sons' newest Steinway Artist.)

But Mitchell wasn’t inclined to dwell on his lengthy (and admittedly prestigious) resume, reminiscing on where he’s conducted or directed. “I’ve been doing this for 30 years now,” he told me, early on in our interview. “And when you get to this point, every interview is the same interview.”

Instead, we focused on the philosophy and lifestyle that shape the man behind the baton.

Photo by Roger Mastroianni

Life Above 7,000 Feet

Mitchell has been married to his wife, Angela, for a little over ten years, and together they have two children, a 20-month-old girl, Rose, and a boy, Will, who turns four on Christmas Eve. His family has lived in the foothills outside Denver, Colorado since 2017, when he was named music director of the Colorado Symphony. “We love living here, because we love the outdoors,” he said.

The family’s home is at 7,300 feet, and backs up to the Bear Creek Highlands. “It's like 880 acres of open green space,” he said. “There are a dozen miles of trails right outside our back door, and it’s sunny 300 days a year, which is a big change, for me, from Seattle.” When the trails are clear, Mitchell and his family are hiking, but when it snows, they strap on snowshoes and hit the trails anyway. “Even in the winter, maybe you get a snowstorm and it dumps a foot of snow on you,” he said, “but the next day is almost invariably a bluebird day, crystal clear, bright blue sky, and we’re out there.”

Beyond the accessibility to pristine nature, there are other advantages, as a performer and conductor, to living in Colorado, Mitchell said. Chiefly, rehearsing at high elevation is a great way to build strong lungs. Mitchell recalled conducting his first concert in Colorado, in 2016. He noticed some oxygen tanks backstage at the concert hall. “I was like, ‘Oh, that’s funny,’” he remarked. “But then I was conducting, I think it was a Tchaikovsky symphony, one that ends big and loud and fast, with lots of energy, and at the end I was really, really winded.” The oxygen tanks weren’t just a gimmick. Players who come to Colorado, he said, will often come a day or two early to acclimate to the elevation.

“There is a reason we train our Olympic teams in Colorado,” he added. “Working out up here, when I go down to sea level, I feel like Superman.”

This passion for an active lifestyle is also what drew Mitchell to Coregami. “Conductors always look for the most comfortable thing possible to rehearse in, attire that breathes, that lets us move the way we want to move. Then we get to the concert hall and we have to put on, well, the most restrictive clothing imaginable!” He laughed. “Coregami figured out a way to rectify that problem.”

Brett Mitchell leads the Colorado Symphony at Boettcher Concert Hall. Photo by Brandon Marshall

More Than Waving a Stick

As a conductor, Mitchell sees his job as multi-faceted, with responsibilities that go far beyond the music. The books on the shelves in his studio, where he sat when we conducted our interview, reflect this. “There are at least as many books on sports psychology and coaching as there are on conducting,” he said. “I’m looking at Phil Jackson, Eleven Rings. Pat Summitt, Sum It Up. Robert Greene, The 48 Laws of Power. I'm looking at John Wooden, at David Brooks, at books about Kobe [Bryant].”

Why so many books about athletics? Mitchell is blunt. “Coaches of professional athletes have the most insight in terms of how to deal with what I deal with as a conductor, which is elite talent,” Mitchell said. “These people are the best in the world at what they do, and they know it. Your job is to make them better, which isn’t easy. So yes, my role is diplomat. It's politician. It's counselor. It's psychologist.”

In fact, Mitchell said his job is “as much about understanding people as it is about understanding music,” if not more, and that it’s not about taking charge and making unilateral decisions, but about organically building a consensus. “While I certainly bring my ideas to the podium, I am not the sole proprietor of good ideas,” he admitted. He added that to the layman, a conductor may seem like a shotcaller. That’s not how it is. “You probably think of this guy standing up there on a box, waving a stick in your face saying, ‘My way or the highway!’ Nothing could be further from the truth,” he said.

Mitchell likened his role to being an “arbiter of taste.” He has the final say, of course, but his voice should be the mouthpiece through which the orchestra speaks. “I try to be as open as I possibly can,” he said. “That give and take is what I love about conducting.”

When I asked Mitchell about some of the quotes or books that have inspired his philosophies on conducting, he was quick to name one by Austrian-born American composer Erich Leinsdorf: The Composer’s Advocate. “This book is great,” Mitchell admitted, “but honestly the title of the book was more revealing to me than anything inside it, because it cuts to the heart of what our job is as conductors. We're advocating on behalf of the composer.”

Mitchell is also fond of a line from the Pulitzer Prize-winning musical Sunday in the Park with George, by Stephen Sondheim, about the work of French painter Georges Seurat. “The line comes at the end of Act II, toward the very end of the show,” Mitchell explained. “Seurat’s in a creative rut, he doesn't know what to do. He doesn't know how to get to the next place. And his muse [Dot] tells him, ‘Anything you do, let it come from you. Then it will be new. Give us more to see.’”

Mitchell loves the quote so much he had it engraved on a piece of wood and mounted on the wall in his studio. This quote was the genesis for what he told me at the beginning of this piece, and it’s a personal mantra for Mitchell, a reminder that, whatever subconscious influences he may absorb as he goes about his life, he needs to be his own artist, for better or worse. As much as Williams, Bernstein, Sondheim, Tchaikovsky, or any other great composer from days gone by may have inspired him, he’s careful never to fall into the trap of emulating their work.

“I want to give audiences something new,” he said.

Brett Mitchell leads the New York Philharmonic at David Geffen Hall. Photo by Brandon Patoc

We’re Here to Show the World What Can Be

Much of Mitchell’s work today involves mentoring young people. He served as music director for the Cleveland Orchestra Youth Orchestra for four years, and has taught at a number of programs for budding musicians. But in an era of generative artificial intelligence—when youth are encouraged to use generative AI for everything from writing essays to creating imagery—he admits that there’s a lot of pressure for youth to mimic. Convincing kids to “let everything you do come from you” isn’t always easy.

Mitchell says that if he had anything to say to the young artists of today, growing up in an era of AI, it’s to not get discouraged. “AI will never be able to stumble upon happy accidents the way humans do,” he said. “AI is trained on the past. It’s trained to take the past, and distill into what it thinks is best for the present. But the most interesting, beautiful things are often those that arrive by accident.” Mitchell often plays jazz in his free time, and remarked on the popular joke that “there are no wrong notes in jazz,” because, “if you hit a note that you didn't mean to hit, all you have to do is take that little mistake and then do it again. Do it again and make it a feature, not a bug. This is something only a human brain can do.”

Another piece of advice Mitchell has for budding orchestral players is to remember that synchronization isn’t the goal. “In orchestras, there’s an emphasis placed on playing together,” he said. “If there's a chord on the downbeat, we all play that chord on the downbeat together. But we have to remember, the end goal is not to play with each other. The end goal is to play for each other.”

He gave an example. “If it's the oboe solo, that may mean the violins need to tone it down, and play more transparently. It’s not just about being in the same place at the same time. It's understanding when it's your turn and when it's somebody else's turn. You have to ask yourself, ‘Am I doing everything that I can to support my colleague?’”

This, Mitchell said, is part of what makes playing, conducting, and listening to orchestral music so special. It’s a collaborative effort, it’s many individuals coming together to craft something beautiful. “Anything that you’re gonna accomplish in your life, if it is worthwhile, you will accomplish it with other people,” Mitchell said.

This is, in part, why he isn’t worried about the future of the arts. Developments in technology like artificial intelligence will take some jobs. That’s only natural. “When’s the last time you saw an elevator operator?” Mitchell joked. But he doesn’t see it ever having a fatal impact on the arts, simply because by nature, AI is retrospective.

“We can't write symphonies with robots. We can't paint pictures with robots,” he said. “Or we can, but the symphonies AI writes, the paintings AI creates, these are just a conglomeration of everything that already has been, they aren’t a lens into things that could be.”

He paused. “We have to remember, that's what artists are here for. We’re here to show the world what could be.”

Brett Mitchell leads The Cleveland Orchestra at Blossom Music Center. Photo by Roger Mastroianni

Brett Mitchell Named a Steinway Artist

Brett Mitchell sits at one of The Cleveland Orchestra’s Steinway & Sons’ Model D concert grand pianos. (Photo by Roger Mastroianni)

NEW YORK — Brett Mitchell has been named the newest Steinway Artist by Steinway & Sons.

In recognition of your distinguished career in music and outstanding commitment and loyalty to the Steinway piano, Steinway & Sons is pleased to welcome you, Brett Mitchell.

The high standard that you have set with your artistic and professional achievements makes it most appropriate that you are now formally included on the Steinway Artist roster, a list of the most accomplished and discriminating artists in the world.

Steinway & Sons congratulates you on receiving this distinction.

Please click here to visit Mr. Mitchell’s artist profile on the Steinway & Sons website.

Review: ‘Jazzy Fun and a Riotous Finale at the Pasadena Symphony’

Music Director Brett Mitchell leads the Pasadena Symphony at the Ambassador Auditorium. (Photo by Courtney Lindberg)

PASADENA — San Francisco Classical Voice has published a review of the opening program of the Pasadena Symphony’s 2025-26 season, Brett Mitchell’s second as Music Director:

Just a week after Halloween, Hector Berlioz’s spooky Symphonie fantastique took center stage at the Pasadena Symphony’s season-opening concert. Outside on Nov. 8, it was an appropriately foggy evening for devilish music. Inside the Ambassador Auditorium, Music Director Brett Mitchell warmed up the hall with a weighty program that also featured sunny jazz-inspired compositions by Maurice Ravel and Jim Self.

Beginning his second season with the Pasadena Symphony, Mitchell enjoys communicating with his audience and provided extensive descriptions and background for each piece, which made for a lengthy but educational evening.

The program’s opener, held special personal significance for Mitchell and the orchestra. Besides his prolific life as a composer, Jim Self was Pasadena’s principal tuba for 50 years (1975–2025) and played in many other ensembles in the L.A. area. He also performed as a veteran studio musician on 1,500 soundtracks for film and television, becoming the “go-to” tubist for film composers. His most memorable gig was providing the “Voice of the Mothership” in John Williams’s score for Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Tour de Force: Episodes for Wind Ensemble was programmed as a 50th anniversary tribute to Self, assuming the composer would be there to take a bow. Sadly, however, Self died just days before the performance, at the age of 82. Mitchell called for a moment of silence in his memory.

The most popular of Self’s 90 published works, Tour de Force was inspired by the European tour he took with the Pacific Symphony in 2006. Scored for a large…ensemble with augmented percussion, it unfolds in nine loosely connected (and not programmatic) episodes. In a note, Self admitted that the piece was “certainly not classical, profound, or groundbreaking,” but “fun, mildly provocative, rhythmically interesting, jazzy, bluesy, and Latin at times.”

The Pasadena Symphony…made a strong case for this rousing and noisy curtain-raiser, which, not surprisingly, draws upon Self's long career in movie scoring for its energy, splashy sound effects, accessibility, and short attention-getting outbursts. The music may not be “great,” but the jazzy atmosphere and dynamic contrasts between larger and smaller groups of instruments made for an entertaining and ear-opening experience.

Tour de Force and the Ravel Piano Concerto in G Major that followed had something in common: the influence of George Gershwin. Episode Five of Tour de Force ends with a “Gershwin-like clarinet solo,” and the piece throughout uses the jazzy “stacked fourth” chords Gershwin was fond of.

Pianist Orion Weiss brought Ravel’s jazzy inflections to the surface of this performance in his delicate, perceptive, and refined interpretation. His account of the sublime second-movement Adagio followed a clear and lyrical line, with shimmering trills and hushed dynamics. Mitchell coaxed fine solo work from the woodwinds, prominent in the spare scoring. The racing downward scales of the final Presto had verve and propulsion, reminiscent of passages from Petrushka by Igor Stravinsky, Ravel’s contemporary in Paris.

Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique requires sustained energy and physical stamina from the conductor, orchestra — and perhaps the audience. Mitchell led with commitment and precision, showing that his connection with the orchestra has deepened since his inaugural season last year…

The work tells a personal story of the composer’s own romantic obsession with the actress Harriet Smithson. Beginning in dreamy infatuation, it progresses, finally to diabolical ruin in a riotous sonic orgy, one of the great climaxes in the symphonic literature… Mitchell and the Pasadena Symphony…managed to capture the drama of Berlioz’s star-crossed journey.

To read the complete review, please click here.

Preview: Pasadena Symphony Emphasizes American Music for 2025–26 Season

Music Director Brett Mitchell stands in front of the Pasadena Symphony’s home of the Ambassador Auditorium. (Photo by Tim Sullens)

PASADENA — San Francisco Classical Voice has published a preview of the Pasadena Symphony’s 2025-26 classical season, Brett Mitchell’s second as Music Director.

In a country as fractured and divided as ours, can a celebration of national pride still sell tickets? The Pasadena Symphony is betting on it.

In anticipation of the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, the orchestra’s 2025–26 season is loaded with American music. Brett Mitchell’s second season as music director will feature two co-commissions and two West Coast premieres by American composers, plus classics by Copland and Dvorak’s America-inspired “New World Symphony.”

“As we close in on America’s 250th birthday next summer, I’m excited to celebrate the best of American orchestral music, past and present, all season long, pairing new American repertoire with great masterworks of the past,” Mitchell said when announcing the repertoire.

The celebration kicks off on Nov. 8 with “Tour de Force,” a piece by Jim Self, the orchestra’s principal tuba. The performance marks his 50th anniversary with the ensemble. The opening concert will also feature two French masterpieces, Berlioz’s “Symphonie Fantastique” and the Ravel Piano Concerto in G Major with soloist Orion Weiss.

Edgar Meyer’s 1999 violin concerto, which incorporates bluegrass elements, will follow on Jan. 24 with Tessa Lark as soloist. It will be surrounded by two favorites by Felix Mendelssohn: his concert overture “The Hebrides” and his Symphony No. 3, also known as the “Scottish.”

Another American work, “Beacon” by Colorado-based composer Jeffrey Nytch, will be presented on Feb. 21. The concert is also set to feature Pyotr Illyich Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony and Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23, with soloist Michelle Cann.

The Mar. 21 concerts will feature a Pasadena Symphony co-commission: the First Symphony of Mexican American composer Juan Pablo Conteras. According to the orchestra, the work is inspired by “his journey to becoming a composer and a U.S. citizen.”

The West Coast premiere of American composer Jennifer Higdon’s Cello Concerto highlights the Apr. 25 concerts with Julian Schwarz as soloist. The program also features Beethoven’s “Eroica” Symphony and the “Heroic Overture” of Dallas-based composer Quinn Mason.

The season concludes with another co-commission and West Coast premiere: the “Rhapsody on ‘America’” by Baltimore-based composer Jonathan Leshnoff, featuring pianist Joyce Yang. The all-American program also features works by John Williams and Aaron Copland.

All concerts will take place at the Ambassador Auditorium in Pasadena, with 2 p.m. matinees and evening repeats at 8 p.m. Subscriptions and single tickets are now on sale.

To read the complete preview, please click here.

Review: ‘Participating in the ritual: Central Oregon’s Sunriver Music Festival’

Artistic Director & Conductor Brett Mitchell leads the Sunriver Music Festival Orchestra in Aug. 2025 at the Tower Theatre in Bend, Ore. (Photo by David Young-Wolff)

SUNRIVER, Ore. — Oregon ArtsWatch has published an extensive review of the final three concerts of the 2025 Sunriver Music Festival, Brett Mitchell’s fourth as Artistic Director & Conductor.

Participating in the ritual: Central Oregon’s Sunriver Music Festival

The joys and miracles of live music in the rustic Great Hall, with SRMF director Brett Mitchell, concertmaster Yi Zhao, pianist and Cliburn medalist Vitaly Starikov, and an orchestra full of stars.

The heat wave that baked much of the Pacific Northwest for a few days last week was in full force as the final concerts of the 48th annual Sunriver Music Festival began. Taking place in the rustic charm of the Sunriver Great Hall, which was once the officer’s HQ at Camp Abbott during the Second World War, the festival took us from Leipzig to Vienna with some strange stops in between…

Monday the 11th was “The Leipzig Connection,” and opened with Schumann’s Manfred Overture; an interesting factoid was that Robert and Clara’s great-great granddaughter was in the audience that night. There was plenty of sturm und drang during the Manfred, and I did my best to hear over the oft-featured horns and woodwinds. The strings were rich and woody, somehow appropriate to this venue as if in a strange “like to like” principle…

Yi Zhao, concertmaster, was the soloist [in Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto], and her cantabile portions were fantastic… She leaned into the sentimentality of the opening movement, and her scalar passages were well-constructed as she was ably supported by the orchestra. The attacca bassoon into the second movement was a delight, and being delighted by the first bassoonist Anthony Georgeson was to become a regular feature of my time here. Zhao wrung the pathos out of the lower registers, sounding very viola-like. The tutti serenade was beautiful… The finale was appropriately spritely and dancing, and Zhao really shone here, as her rapid-fire sautillé toward the end positively sparkled. I’m not sure what the classical music scene as a whole is like in Central Oregon these days, but since the demise of the Cascade Festival of Music, I imagine there are not many other chances to hear tremendously important works of this caliber in the region.

Sunriver Music Festival Orchestra Concertmaster Yi Zhao and Artistic Director & Conductor Brett Mitchell. (Photo by David Young-Wolff)

Earlier in the first half, conductor and Artistic Director Brett Mitchell (read his interview with Matthew Neil Andrews, and get more detail on the festival and venue here) mentioned that anyone who achieved a certain level of piano aptitude likely learned some of Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words at some point in their playing career. Those ones escaped me, but us little Baroque boys instead sometimes learned a piano transcription of the work that opened the second half, the now-(though not always)-famous Toccata and Fugue in D Minor BWV 565 by good old Uncle Bach, the great Johann Sebastian. Originally composed for the organ (though there is apparently some argument as to whether Bach himself actually composed it), the work languished in relative obscurity until Leopold Stokowski’s famous orchestral transcription appeared in Walt Disney’s Fantasia about the time the Sunriver Great Hall was being built. Mitchell pointed out that the number of musicians required to play that particular transcription might be almost equal to that night’s orchestra plus all the members of the audience, so the rendition played here was Australian composer Luke Styles’ brilliantly scaled-down version for percussion, strings, and a small wind section.

A startling simultaneous trill on tambourine and triangle underpinned an abrupt and almost comical exposition of the famous toccata theme by the winds at the opening. The huge, menacing chords built from the ground up by the winds were fantastic, and the woodblock chattered behind arpeggiating strings. Gently the strings carried the majority of the fugal opening, and the descending scales were parted out to various instruments in clever salvos. The percussion accents were various and vital, and all in all this work with its light touch and deft instrumentation was a breath of fresh air for those (like me) who consider Stokowski’s version weighted and a bit stodgy.

The finale of the evening was Bach’s Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major BWV 1068, the perfect piece for a summer music festival, right up there with Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks or his Water Music suite. Mitchell led the orchestra deftly in a marvelous rendition of the “Overture,” this gem of stylized Baroque grandeur at its finest with its succinct trumpet fanfares set one after another in a filigree of majestic fortissimo timpani rolls. In the second movement, whose main theme is sometimes known as the Air on the G String, the strings played this timeless melody in a broad, handsome largo. In the Gavottes the interpolations from the principal trumpet Jeffrey Work ended with breathtakingly gentle terminal trills, in opposition to the wide, bold cadential trills he delivered later in the Gigue. The evening left me excited for more of the festival, and ready for whatever peregrinations would lead us to Vienna for the final evening…

Brett Mitchell leads the Sunriver Music Festival Orchestra at the Great Hall in Sunriver, Ore. (Photo by David Young-Wolff)

Miracles

The final night of the festival took us as promised to Vienna, after the ethereal and mystical stops of the previous evening. The evening opened, appropriately enough, with a work by Haydn, Symphony No. 96 in D Major, Hob. I:96, also nicknamed the “Miracle.” The opening was appropriate because the other great Viennese masters Mozart and Beethoven were also programmed this evening, and Haydn was at one point Beethoven’s teacher, and was a friend and mentor to Mozart for most of the latter’s life, with Mozart even dedicating six of his string quartets to “Papa Haydn”…

The SRMF’s performance featured some magical moments. Principal oboe Lindabeth Brinkley was absolutely top-notch: her delicacy of phrasing, her ability to combine the sweet with the powerful during the opening “Adagio” made me wish that movement would never end. The winds generally were fantastic while I was there; the little trios and quartets that manifested themselves here and there were constantly among the highlights of any performance. The fine tutti sections in the finale were strong, punctuated without being overblown, and the finesse required from the brass and winds to deliver a first-rate performance was everywhere in evidence.

Much as it had been at The Cliburn earlier in the summer, it was a true pleasure to hear Vitaly [Starikov] play multiple concerts in one week, and his back-to-back performances at SRMF were a highlight of my year. He chose the Piano Concerto No. 17 in G Major, K. 453 to play at the SRMF…

In the “Andante” the woodwinds again showed their caliber: the very highest. They displayed unity and precision in an almost uncannily unified timbre to come from such disparate instruments; if I have ever heard a more dulcet bassoon than Georgeson playing the Mozart that evening, I can’t remember when it was. The soloist played misterioso, giving this movement everything we love about a Mozart andante; it was soulful and hauntingly melodic. He has a sensitivity to his attack, a way of leaning into the instrument and bringing his hands down in such a way that it feels like he is going to disgorge some frightfully loud chord – and then he puts all that tremendous energy into the softest cantabile imaginable…

My friend Jon was with me for both the Leipzig and Vienna concerts. He is a musician himself, and we shared our insights with one another throughout the week. He commented that he thought a really great soloist can raise the level of the orchestra, and I agreed with him, and in this case, I thought that two things were going on; that is to say there was a feedback loop between soloist and orchestra, as though each kept upping their game, as if each were daring the other to do better. The orchestra was spectacular in this work, and I was as impressed with Starikov’s Mozart as I was with his solo work, which is about the highest praise I can think of.

Pianist Vitaly Starikov and conductor Brett Mitchell after performing Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 17 with the Sunriver Music Festival Orchestra. (Photo by Jimena Shepherd)

Talk about your all-time festival favorites, what better way than to round off the festival than by playing Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op 67…

The opening four notes are maybe the most famous four notes in music history, and their execution is something of a matter of personal choice by the conductor. Mitchell chose here to launch straight into it with no fanfare, no ritardando or undue accenting: he simply played them as they were written: the opening bit of an “Allegro con brio,” and this worked really well. Let’s not milk it, I thought, there is so much other great stuff here, and we will get to hear this motive many more times tonight. The brisk tempo was also a great choice, and the strings were obviously having great fun – this was their chance to shine, and the phrasing was nuanced and intelligent, with sensitive piannisimi, giving the music plenty of room to grow dynamically.

I began to note various things live that I maybe don’t pay as much attention to when I listen to a recording. Things like the bitter battles between strings and winds, the importance of the bassoon as an anchor to the harmonies, the small but vital horn entrances on which the ensuing parts hang. In the “Andante con moto” I noticed just how difficult the contrabass parts were, and how much fun the double bassists Jason Schooler and Clinton O’Brien had on their fortissimo cadential endings, the one-note whomps! they got to play at the end of a phrase… I heard how the cellos and violas sounded at times delightfully like a collection of woodwinds; their ability to change color, chameleon-like in this fashion is something I don’t note unless I’m sitting there, reveling in the glory. The sudden and surprising crescendi, the tootling piccolo hits in the “Scherzo” – the list goes on and on.

As the Beethoven ended, I pondered the incredible possibilities and synergies that develop when performers and audience gather at the same time, to participate in the ritual, the very real magic known as live music. Though this was my first time attending, the Sunriver Music Festival, in its 48th year, feels like the gift that just keeps on giving. Here’s to 48 more.

Brett Mitchell and the Sunriver Music Festival Orchestra after performing Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5. (Photo by David Young-Wolff)

Feature: ‘From Manilow to Mozart, Sunriver maestro Brett Mitchell is an all-around music fan’

Brett Mitchell leads the Sunriver Music Festival Orchestra (Photo by David Young-Wolff)

BEND, Ore. — The Bulletin has published a feature about the Sunriver Music Festival and its Artistic Director & Conductor, Brett Mitchell, who is about to begin his fourth season at the helm of the nearly-50-year-old festival in Central Oregon.

Sunriver Music Festival kicks off Saturday, with four classical concerts, a family concert and the ever-popular, and often sold-out, pops concert over the next week and a half in Bend and Sunriver.

The festival opens at the Tower Theatre with an evening program titled “A French Soiree,” followed by the Pops Concert Sunday night, also in the downtown Bend theater.

Concerts continue apace, through Aug. 11’s Season Finale Classical Concert, “Vienna Waits for You,” with music by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, among the many composers who called the Austrian city home.

But if, like Brett Mitchell, conductor and music director of the seasonal classical festival, you’re a Billy Joel fan, you know that the concert’s title is a pulled directly from the lyrics of “Vienna,” the B-Side to Joel’s 1977 single “Just the Way You Are.”

“I really am a subscriber to Duke Ellington’s great aphorism, which is, ‘There’s only two kinds of music. There’s good music, and there’s bad music,'” Mitchell said.

First came rock

Mitchell’s classical bona fides include his service as current music director of the Pasadena Symphony, and previous stints as music director of the Colorado Symphony, associate conductor of The Cleveland Orchestra and assistant conductor of both the Houston Symphony and Orchestre National de France. In May, Mitchell stepped in for conductor Juanjo Mena and made his subscription debut with the New York Philharmonic with less the 24 hours’ notice, receiving wide praise in reviews of his work.

But Mitchell is also a rock and pop aficionado. The array of autographs on the wall of his home studio attests to his wide and varied musical influences and tastes:

“I’m in my studio right now, and I’ve got to my left what I call my autograph wall, and I’ll tell you who’s autographs are on this wall,” Mitchell said. “The autographs are Stephen Sondheim, Leonard Bernstein, John Williams, Billy Joel, Barry Manilow, Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel and Tony Bennett.”

If there are any aesthetes turning a nose up at the very notion of this diverse group sharing space on Mitchell’s wall or playlists, know this: He grew up in a non-musical family, and from a young age, rock and pop were his entry points into what he does professionally now.

We mean very young.

In the early ’80s, when he was 3 years old, he heard a song on the radio and asked his mom, who was getting ready for work, if they had it on vinyl.

“She said, ‘We do have a record of it.'”

Mitchell told his mom he wanted to take said record and his Fisher-Price record player to his caretaker, Janet’s house. His mom said Janet probably already knew the song. But he was determined to do it his was. His mom gave in on the record, but told him Janet has her own record player.

“I said, ‘No mom, I really want to take our record and my record player.’ And rather than argue with a 3-year-old, which is never a winning proposition — which I can attest to because we have a 3-year-old right now — she said, ‘OK.'”

Oh Mandy

When they arrived at Janet’s, the future conductor stopped his mom from leaving to head to work, he insisted the three of them sit together and listen to it.

The record: “Mandy,” Manilow’s 1975 no. 1 song, in which Mandy came and gave without taking. “The thing I have up on my wall — there was a silver record released for ‘Mandy’s’ 40th anniversary like 10 years ago, that Barry signed however many of.

“It’s funny, because people hear, you know, Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim, John Williams up on my wall with the silver record of ‘Mandy’ by Barry Manilow, and it’s like, ‘Guys, this is what I’m talking about,'” Mitchell said. “I tell that story all the time because it’s a cute story … but here’s what it really is. I found music that I loved, and I wanted to share it with as many people as I could.

“Now, when I was 3, that was for my mom and my caretaker on a living room floor in Seattle,” he added. “Now I get to do it — I opened the Cleveland Orchestra’s Blossom season (that’s the name of its summer performance venue) for 20,000 people a couple of weekends ago. So when you ask do I listen to pop, I do listen to pop. I listen to jazz. I listen to almost everything but classical to be honest with you, because I’m always working on classical music. That’s what I do all the time.

“The last thing I want to do when I’ve finished a day of studying Mozart is go listen to more Mozart. I’d much rather listen to Dave Brubeck and Bill Evans.”

The early ’90s

Knowing he was 3 in the early ’80s and living in the Pacific Northwest, you can probably guess what genre he got into after the smooth rock of Manilow.

“I was born in 1979 in Seattle,” he said. “By the time I got to middle school in 1991, it was Nirvana, it was Pearl Jam, it was Soundgarden.”

Crack open his middle school yearbook to “whatever page you want, every one of us is in flannels and ripped jeans,” he said, laughing.

He’s chiefly a Nirvana guy: “I thought Nirvana was as good as it got.” He even preferred the raucous, Steve Albini-engineered “In Utero” over the polished, Butch Vig-produced breakthrough “Nevermind.”

For him, there’s a common thread among all the songwriters and composers he’s come to love in his work and his free time that ties it all together.

Because of the way Mitchell had always viewed music, when he began exploring classical at age 15, “It didn’t strike me as any different from Nirvana,” he said. “Here’s a guy dealing with some serious things in his life, and has chosen, as part of the way that he’s going to work through these things, he has chosen to share that with the rest of us, to make the rest of us feel less alone. That’s exactly what Kurt Cobain was doing. That’s exactly what Beethoven was doing.”

“To me, it’s all the same,” he said.

Brett Mitchell to Debut with Memphis Symphony Orchestra in October

MEMPHIS — The Memphis Symphony Orchestra has announced that Brett Mitchell will make his subscription debut with the ensemble this fall, leading the following program:

MASON BATES - Philharmonia fantastique

BERLIOZ - Symphonie fantastique

The program will be presented on Saturday, October 25 at 7:30 PM at the Cannon Center for the Performing Arts and on Sunday, October 26 at 2:30 PM at the Scheidt Family Performing Arts Center.

For more information, please click here.

Brett Mitchell Returns to The Cleveland Orchestra in February 2026

Brett Mitchell will lead two performances of Michael Giacchino’s Oscar-winning score for Up with The Cleveland Orchestra in February 2026.

CLEVELAND — The Cleveland Orchestra has announced that Brett Mitchell will return to Severance Music Center in February 2026 to lead two performances of Michael Giacchino’s Oscar-winning score for Up.

Two performances will be presented:

Friday, February 13 at 7:30 PM

Sunday. February 15 at 3:00 PM

For tickets and more information, please click here.

Feature: ‘Falling in love with music: A conversation with Sunriver Music Festival artistic director and conductor Brett Mitchell’

Photo by Roger Mastroianni

BEND, Ore. — Oregon ArtsWatch has published an extensive feature about the Sunriver Music Festival and its Artistic Director & Conductor, Brett Mitchell. The article features a substantial interview with Mr. Mitchell, who is about to begin his fourth season at the helm of the nearly-50-year-old festival in Central Oregon.

Falling in love with music:

A conversation with Sunriver Music Festival artistic director and conductor Brett Mitchell

Mitchell, now in his fourth season with the Central Oregon summer festival, discusses how his background as a composer informs his approach to conducting, why performing in Sunriver feels like coming home, and the immersive future of classical concerts.

Preparing to interview Brett Mitchell — conductor and artistic director of the Sunriver Music Festival, which starts August 2 and runs through the 13th — a few big questions came to mind. First: what is it that a conductor does, exactly? Beyond the time-keeping arm-waving and expressive emoting we all associate with the job, that is. Second: what goes into planning a seven-concert music festival in a resort town? It’s just the right length to be really difficult, in the sense that planning a single concert is hard but manageable, whereas planning a big long festival (like Chamber Music Northwest or the Oregon Bach Festival, say) is a lot more work by volume but also comes with a certain amount of wiggle room in terms of the longer arc.

Turns out, Mitchell had answers to all of these questions and a lot more…

Born in Seattle, studied with Leonard Slatkin, worked with Kurt Masur and Lorin Maazel, did The Lenny Thing and conducted the New York Philharmonic as a last-minute replacement (read those reviews right here). Basically your standard superstar conductor success story. He now lives in Colorado, where he ran the Colorado Symphony in Denver for five years, and currently leads the Pasadena Symphony. Since 2022 he’s been head honcho of the Sunriver Music Festival.

So much for the conducting credentials. During the pandemic he brushed up his piano chops, started having kids, and renewed his youthful interest in composing–an interest he’d mostly left behind when he had to choose career paths in grad school. Five years later and his YouTube channel has dozens of videos: Bartók, Chopin, Glass; massive amounts of film music (he was all dressed up to record Jaws when we spoke earlier this month); and a few samples of his own original work.

Mitchell’s original music was mostly written (or arranged) for his children, and a few pieces were sung by his wife Angela. Here’s “Love You Forever” (written for the first baby, Will):

And here’s Mitchell’s “Nocturne”:

And here he is playing Billy Joel’s “Nocturne”:

And here’s some Star Wars:

And here he is conducting Petrushka in 2016:

Got it? Good, then let’s go.

The following interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity and flow.

Oregon ArtWatch: Let’s start with your a-ha moment. What switched the light on for you as a musician?

Brett Mitchell: Thank you for leading with such a fun question. I do have an a-ha moment. I have a few of them as you would imagine, but there’s one that I always point to. I was born in 1979, and I was a little, little kid in the early ‘80s. It was just me and my mom at that point, and my mom was getting ready for work one morning and this song came on the radio, and for whatever reason it just grabbed me. I went into my mom’s bathroom where she was getting ready, and I said, “Mom, what is this song?”

And she told me what the song was. And I said, “do we have a record of this song?” And she said, “We do.” And I said, “Okay, here’s what I want to do. I want to take our record of this song and my little Fisher Price record player that you bought me for Christmas, and I want to take it to Janet’s house” (I used to stay with a caretaker named Janet) “and I want to play the song for Janet.” And my mom said, “well, you know, sweetheart, this was a number one song for a long time. I’m sure Janet knows the song.” I said, “yeah, mom, but I really want to play it for her.” And she said, “OK, well, how about this? Let’s take our record. Janet has a record player, we’ll play it on hers.” And I said, “No, mom, I want to take our record and my record player.” And rather than arguing with a three-year-old, which as a parent of a three-year-old right now I can tell you is not a winning proposition, we grabbed the record and the record player and we went to Janet’s house. And my mom said, “okay, sweetheart, I’ll see you tonight.” And I said, “where are you going?” And she said, “well, I have to go to work.” And I said, “no, mom, I want us all to sit here and listen to it.” And so we all sat there in this living room and listened to Barry Manilow’s “Mandy.”

Mitchell: Of all things, that is not where you thought this story was going! For whatever reason, that song really grabbed me. I mean, to the point where I have up on my wall the silver record signed by Mr. Manilow himself. It’s funny because I tell that anecdote a lot, and it’s cute, and it always gets a good laugh, but what it really illustrates is: It’s the exact same thing that I do today, which is find music that I love and then share it with as many people as I can. If that’s two people in a living room in Seattle, great. If it’s 20,000 people at some outdoor venue at a summer festival, great. It doesn’t matter to me.

Certainly it’s a long leap from “I heard a pop song from the ‘70s” to “I want to conduct the New York Philharmonic.” But at the same time, music is music. Falling in love with music is falling in love with music. There’s a lot of different ways that you can fall in love with music, and a lot of different avenues that that love can channel itself through. But for me, that was the moment that I was like, “okay, this is obviously something very special.”

I also remember from right around that same time, we had a piano at our house later but we didn’t have a piano when I was first growing up. But my mom’s aunt and uncle did in Roseburg, Oregon, and we would go visit them, and I remember being around that piano for the first time, and I remember playing the very highest notes on the piano. I was, again, about three or four years old. And because of the “tinkle, tinkle, tinkle,” I thought, “oh, Three Little Pigs, that’s fun.” And then I went down to the low end and I kind of rumbled down there and I thought, “oh, Big Bad Wolf.” So something about the storytelling potential of music got to me really early.

I grew up in Seattle and when I was at those really peak formative years of middle school that’s when grunge hit. Go back and look at my middle school yearbook from the early 1990s every one of us is in flannels. I really didn’t get to Beethoven until a few years later in high school, but the really nice thing about viewing music the way I’ve always viewed music is that I heard Nirvana and now I’m hearing Beethoven and they don’t sound super different to me. What it sounds like in both of these particular cases is a guy going through some really challenging times, really challenging things, and trying to work it out through his art, through his music. And by doing that, the rest of us that have had those experiences feel less alone, because somebody else is giving voice to the things that we’re experiencing. The crux of music, the whole purpose of music is communication. And composers in particular are only trying to communicate. They’re only trying to feel, to get us to feel what it is that they are feeling at that moment.

That’s the infinite power of music: it doesn’t really matter. Duke Ellington said there’s only two kinds of music, good music and bad music. That’s it. It doesn’t matter whether you call it symphonic or jazz or pop or emo or ska or whatever. Good music is good music. And that’s all we’re looking for.

OAW: Could you describe the nuts and bolts of what a conductor and artistic director does? We all know that it’s more than the arm waving, but what really goes into the work?

Mitchell: Well, the first thing I would say is that there’s the conducting part of the job, and then there’s the music directing part of the job, or the artistic directing part of the job. My title with Sunriver is “artistic director and conductor,” which implies two different things, and in fact it is two different things. As artistic director or music director, depending upon the organization, you’re in charge of the artistic direction of the organization. That means that I decide what the repertoire is that we’re going to play, what the music is that we’re going to play every season. I decide who the soloists are going to be, who are we going to bring in for some of the concertos that we do, the solo pieces with orchestra. I handle a decent amount of the administrative things that go along with any position.

As for the conducting part of things, what I’m essentially there to do is to help all of these highly trained professional musicians–who are looking in any given rehearsal or performance only at their part–to help them understand how their part fits in with everybody else’s part. You see the first flutist is looking at music that says “Flute 1,” and it has all of the music for the first flute. Same for the second flutist, same for the first oboist, the clarinetist, the bassoons, the horns, the violins, they’re all just looking at their own music. They don’t know what the horn player has in that bar because it’s not provided for them. I mean, if everybody had all of the music all of the time, the music would have to stop every 10 seconds so everyone could turn the page, right? It doesn’t really work like that.

So I have the great luxury of not having to learn how to physically, technically execute all of that music. I have to be able to look at the score, which is the document that I have that has everybody’s parts in it. It’s got the first flute and the second flute and the oboes and the clarinets and the bassoons. And so I’m able to see the context. I’m able to see what the musicians don’t see. Musicians are such good colleagues that we tend to always have our ears open, and when we find somebody else that we’re doing something with we try to mimic them. You’ve got a whole note in this bar, but the person sitting over there has a half note, and you think “if they’re exiting at this moment then I should probably be doing that as well.” And the answer is “no you don’t”–but where does that answer come from if you don’t have somebody at the center of it all that’s aware of the hierarchy at any given moment?

If you think about any pop song, there’s the melody that’s sung by the lead singer, but there’s also the drum track, the bass track, the keys track, the guitars track. All of that has to get blended together in a recording session. That’s the job of the engineer and the producer. I am the engineer and the producer when it comes to the orchestra.

I am what I would also call the arbiter of taste. If the score says “loud,” well, what what does “loud” mean? Does a “loud” in Mozart mean the same thing as a “loud” in Tchaikovsky? If it doesn’t, how are they different? Why are they different? So my job is to decide how loud is loud, how soft is soft, how fast is fast, how slow is slow, how long is long, how short is short, and to make sure that everybody is operating under the same rubric. If we’ve got 50 people on stage performing a Beethoven symphony, we might have 50 different opinions of how Beethoven should go. My job is to say, “for this performance, for the sake of intelligibility to the audience, everybody can’t just do what they want. We all have to be at the same place at the same time in the same way.” And I’m the guy that makes sure that all of those things happen. That’s a very high level look at what I do.

OAW: So then how would you characterize your own specific approach to conducting? What makes you different from any other conductor?

Mitchell: Part of what makes me different from any other conductor is that I’m me. We are all who we are as individuals, and you can’t separate who you are as a person from who you are as an artist. It’s a very physical thing that I do; I also contend with my body. We are all trapped in our own bodies. And even if I wanted to look like another conductor, even if I wanted to make a gesture like another conductor, I can mimic it but that’s his body or her body and it’s gonna look and feel more natural to them than it will to me.

So that’s part of the path of learning conducting: absorbing all of these other influences and then saying, “okay, but I’m my own person and I’m in my own body and this is what I have to work with.” So some of the individuality comes purely by you being an individual, and there’s nothing that we can do about that.

I would say that one of my defining characteristics as a conductor really stems from my background as a composer. My undergraduate degree is in composition from Western Washington University up in Bellingham. And when I started, I did not set out to become a conductor. That was not even on the radar. I started conducting by conducting my own music.

My high school band director commissioned me to write a piece the summer between my sophomore and junior years. And then we got to junior year, I had written the piece, and she said, “well, why don’t you just conduct it?” And I said, “because I don’t know how to conduct.” And she said, “yeah, but you know the most important thing about conducting this piece, which is you know this piece.”

And that’s what you really need. If you think about a word like “authority”–to have authority up on the podium, what does that really mean? Authority does not come from standing up on a box. I really think about the root of the word: If I want to have authority on the podium when I’m working on this piece, that means I have to know this piece so well that I could have authored it. That is what being an authority is. You know the thing so well that you may as well have written it yourself.

And listen, I’m a pianist and I am guilty of this when I am a pianist–as many musicians are–of ignoring markings that exist in the music, because I don’t want to do that at that exact moment. Well, okay, fine, but it’s not really about “want to.” The “want to” has to be serving the composer, because if the composer didn’t write this piece then we don’t have anything to do. The musicians don’t, I don’t, nobody does. So if we’re not there trying to serve the composer’s vision, then what are we there trying to do? What that means for me is that I take composers very seriously. And I take composers at their word. Now that doesn’t mean that I’m a slave to the score, that I don’t bring any imagination or thought. I understand that composers want us to use our imagination within what they have laid out for us. But I’m never casual about if. If a composer says that something should be done at, you know, half note equals 104, that’s the tempo the composer wants. Maybe I’ll be 96, maybe I’ll be 100, maybe I’ll be 108, maybe I’ll be 112. But I’m certainly not going to be 72. And I’m certainly not going to be 138.

And so I think part of what defines my approach is a real respect for and reverence for the composer and taking composers seriously and taking composers at their word.

Shakespeare had a great, very short line, which was “speak the speech.” You know what I mean? Just say it, just say the words. David Mamet, a great playwright and director, had a book about acting. He said, “you have to stop with the funny voices.” He said, “if the speech is good, nothing that you put on top of it will make it better. And if the speech is bad, nothing you put on top of it will make it better.” So, what that tells you is, the speech is the speech. The score is the score. You have to trust that the words in the play are going to connect with the people who hear them. And you have to trust that the notes at the concert are going to connect with the people who hear them. But the only way that you can make sure that the composer’s intention is being met is by doing what the composer asks you to do, even if it sometimes feels wrong, even if it sometimes feels awkward, even if you don’t quite understand why. I think presuming that we know better than the composer is a slippery slope and dangerous territory, and I don’t think I’ve ever gone against a composer’s wishes and felt like, “yeah, I showed him.”

That’s not the job. That’s really not the job. This is not a creative art, what I do. It is a re-creative art. I am taking music that is in printed form in these scores and with my colleagues trying to bring that music to life. But I’m not inventing the music. The players aren’t inventing the music. That’s already been done for us. So maybe that sets me apart from some of my colleagues.

OAW: What led you to then focus on conducting, rather than focusing on composing or playing piano?

Mitchell: My undergrad, as I mentioned, is in composition. I’ve always played the piano. And then I started conducting 30 years ago this fall, in October of ‘95. And it was just a practical thing. It was just my teacher saying, “hey, you should conduct this thing.” Not, “I’m gonna write this piece and finagle my way onto the podium.” That wasn’t the thought at all.

Mitchell: When I got to college, I started writing bigger and bigger pieces, and the bigger the piece you write, the more likely you are to need a conductor. So I started conducting more of my music in college. And then my colleagues in the composition program, my fellow composers, would say to me, “look at that, Brett conducts. Hey, you want to conduct my new piece?” And I’d be like, “yeah, sure, why not?” So I would conduct my friends’ music. And it became clear that I had a natural affinity for helping to shepherd what was going on.

And I knew as I was approaching the end of my undergrad that I was going to have to pick something. If you’re going to go to grad school, you’ve got to major in something. You have to get a master’s in something. You can’t get a master’s in everything.

I think my natural talents are part of what I have to offer: leadership ability. And you really need that as a conductor in a way that as a pianist you do not, and as a composer you do not. It’s also true that being a pianist, you spend hours and hours alone practicing, and you often go on stage alone. As a composer, you spend hours and hours alone writing, and then often you just give the music to other people and you’re not even part of the fun.

And as a conductor, certainly I spend hours and hours alone studying, but the penultimate result is that I get together with my colleagues in the orchestra, and we get to work for a few days on this music that I’ve been studying, and then we get to perform for an audience. I love working with other people, and I love performing for an audience, and given the musical spheres that I was in, it made sense to become a conductor.

And so that was really what I exclusively focused on from the time I was about 22 until I was–well, let’s see, I was 40 when the pandemic started. And when the pandemic started, I was stuck at home, as was everybody. And I was so kind of unmoored, because I couldn’t make music. Conductors, we need an orchestra. Orchestras just shut down because you, I mean, think about what an orchestra is. It’s a bunch of people blowing into their instruments. This is not what we wanted to do during COVID times.

I’ve always had a very clear mission statement, which is to share music I love with as many people as possible. And I was complaining to my wife a few months into the pandemic about how I wasn’t able to make music. And she said, “what does your mission statement say?” And I said, “to make music I love for as many people as possible.” And she said, “and where in there does it say anything about an orchestra? Where does it say anything about an audience? Where does it say anything about conducting?” And I was like, “you’re just constantly right.” She was, she was exactly right.

And so while I had played some piano over the intervening 20 years or so, I really got my chops back up once the pandemic started. I started arranging things. I started arranging film scores, scenes for piano, because that was a thing that I was able to do that nobody else was doing. I have conducted a lot of movies live to picture, so I had access to these scores. I have a composition degree, so I’m able to look at a big orchestral score and reduce that for piano. I am a pianist, so I can play those things on the piano. I understand how it works to try and line music up with picture.

Editing the audio, editing the video–that was a whole new thing. That was a challenging thing. But like many, many, many, many people, I figured out how to do that. As with, you know, virtually everything on the planet, COVID forced a readjustment of priorities. Now I find myself conducting all the time again, thank goodness. But I also do have a good following on YouTube, and I want to keep that going. Not because it makes me so much money, but because the people who are on there, who enjoy what I do on there, really enjoy what I do on there. I appreciate that a lot, and I enjoy doing it as well. I’m going to go record a video right after this interview, for Jaws‘ 50th anniversary.

Mitchell: I’m always suspicious of people who say, you know, “I knew from the time I was eight years old that I wanted to be a conductor.” When you’re eight years old, you don’t you don’t really understand what’s going on up there. You see somebody that’s the center of attention and standing on a box and waving their arms and apparently all-powerful. But that is about 1% the truth of what actually goes on up there. I think it’s much healthier if you sort of backdoor your way into it the way I did.

OAW: Could you talk about your composing life, what you’ve been working on and sharing on YouTube these last few years?

Mitchell: Almost everything that I’m composing now is actually not composing, it’s arranging. I would say that the composing that I’ve done over the past few years, with a couple of exceptions, has really been for our kids. We have an almost three-and-a-half-year old boy–a week from today he’d want me to tell you–who just started preschool last week, who’s very excited about that. And a little girl who just turned one back in April. When they were coming into the world, I thought “well dear God, I’m a musician. I’m a composer, I’m a pianist, I can’t not do something for them.”

So I repurposed a lullaby that I wrote back when I was either 15 or 16 and I called it “Will’s Lullaby.” I’ve actually never written it down anywhere; it exists on the YouTube channel, but I’ve never written it down anywhere.

And because my wife is a soprano, we also wanted to do a song for Will. And I had written a song maybe 20 years before for a colleague of mine who had a baby, and that was “Love You Forever.” And I said, “I want to make it a little bigger and a little more expansive.” And so I sort of rearranged that when Will was born.

Will was born Christmas Eve of 2021. Rose was born in April of ‘24, and her little lullaby was from another piece that I had written back in the year 2000 called “Four Miniatures for Solo Piano.” It was just the second movement of that. Again, I expanded it, changed it around a little bit. But I needed to find a new text, because I had run out of old music to repurpose.

We knew we were going to name her Rose. I’m Brett William, so our son is Will. My wife is Angela Rose, so we knew her name was gonna be Rose once we found out it was a girl. So I went looking around for rose poems and found a great poem by Robert Frost called “The Rose Family.”

Mitchell: I’ll tell you the really interesting thing about all four of those. My wife and I just did a recital together here in Denver last month, and we played all four of those things. I played “Will’s Lullaby,” we sang “Love You Forever,” then I did “Rose’s Lullaby,” and then we did “Rose Family.” And “Will’s Lullaby” was written, as I said, when I was 15 or 16, and “Rose’s Lullaby” was written when I was like 20 and towards the end of my composition degree. And one of our neighbors who came to the recital, a big music fan, she said, “I have to tell you, I really liked ‘Will’s Lullaby’ a lot. I think I liked that more than ‘Rose’s Lullaby.’” And I was like, “that’s very interesting because what you’re saying is that the music of the essentially relatively untrained 15-year-old was more palatable than the music of the trained 20-year-old.”

And I completely understand that. I really do. I totally understand where that’s coming from. When you’re in the middle of getting a composition degree, you want to be taken seriously, you want to explore all the different ways you can create music and sound worlds you can make. When I was writing “Will’s Lullaby” when I was 15, I was just writing a pretty tune, because that was all I was interested in doing then. And as it turns out, people are mostly interested in the pretty tune. I found that really interesting, and I didn’t take offense to it at all.

So most of the composing that I do is really in the guise of arranging for the YouTube channel. But then I’ll also write little things here and there, usually as gifts for people. Leonard Bernstein used to write little pieces for people that he called “anniversaries.” And it was either for an anniversary or a birthday, just little teeny tiny gifts. And then I think after Lenny died, they were all published together in three different sets or something like that. But it was never intended to be that. It was just intended to be, “hey, I love you.” Some people like to cook for other people. I like to write music for other people. It’s no different. It’s a love language coming from me.

OAW: Let’s talk about Sunriver Music Festival. How did you get the job in the first place, and what’s it like putting together a music festival?

Mitchell: I got a phone call, or maybe an email, at the beginning of a pandemic about this festival that was looking for an artistic director and would I be interested in applying. I think somebody may have recommended me for it. And I said, “sure, why not?” And ended up coming out during the summer of 2021. I was one of two candidates that they brought in to lead half of the festival. I led half the festival that year and they offered me the position and I took it. So this will be my fourth season.

The thing about a summer festival is we spend so much of our year working with the same people week in, week out. So there’s something really nice for musicians about going on the road for a couple of weeks, going to a really beautiful place like Sunriver–that’s certainly part of why we’re able to attract the caliber of musicians that we’re able to attract is, because we have a festival in a beautiful place–and to come together and to make a whole bunch of music in a relatively short period of time.

I’m always listening to the audience and what the audience is saying they want to hear, because that’s important. I’m listening to the board, I’m listening to the musicians. What do they want to hear? What do they want to play?

And then I’m really balancing that with the simple truth, the practical reality of how these festivals work. I’ll give you an example. If we have a show on Sunday night, the way that the rehearsal schedule usually works for it is we rehearse Saturday morning, Saturday night, Sunday morning, show on Sunday night. So we start at 10 a.m. on Saturday morning and 36 hours later, 10 p.m., we’re done with the program and we’ve done three rehearsals and the show. That is a tall order for anybody.

Part of what that means, and this aligns nicely with the summer festival, is that the programming has to be a little bit more conservative. You can’t just go totally crazy with these people who don’t play together for most of the year. So part of it is just getting our sea legs in terms of how we listen to each other. But then also being realistic about how much time we have to put this program together. And so I have to be very cognizant of all of those things.

So on our first program this year, there’s a couple of pieces that the orchestra could play, you know, blindfolded backwards in their sleep upside down. The selections from Carmen, I mean dear God, we have all played Carmen thousands of times in our career. No problem. The Ravel Piano Concerto, professional musicians play that all the time and we love it. And then there are a couple of pieces that are slightly more off the beaten path, but nothing that’s gonna cause the musicians any challenges. The Fauré, Pelléas et Mélisande, is one of the most beautiful pieces on the planet. And then the opening fanfare is a piece that doesn’t get played a lot. It’s also not terribly long, but it’s a great way to show off the brass section.

I’m trying to take all of the constituencies that we’re trying to serve. I’m trying to serve the audience. I’m trying to serve the musicians. I’m trying to serve the board for whom I work. I’m trying to serve myself because I have to believe in what we’re doing up there. Making sure that all of those different constituencies are being served and that we’ve got real variety over the course of the season. That’s the other thing that I think is really, really crucial.

That opening program is all French music. The next classical program is a classically oriented program: There’s Mozart, which is pure classical music; there is Tchaikovsky doing his Mozart impersonation; there is Stravinsky doing his Mozart impersonation; and there is Bill Bolcom doing his Mozart impersonation. So all of these pieces go together in a not haphazard way–they go together in a very intentional way to make sure that what you just heard is a little different from what you’re about to hear, but somehow related. That the concert you heard a few days ago is different from what you’re hearing tonight. I mean, how much more different can you get from an all-French program than the way we close with Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven? The height of what we would call the Viennese school, Viennese classicism. And then in the middle of all of that, you’ve got this beautiful trip to Leipzig with Robert Schumann, and Mendelssohn with our concertmaster, and then a couple pieces by Bach.

And we haven’t even touched the family show, we haven’t talked about the pops show. So there’s all sorts of music that occurs over the course of the season with the intent of serving all of us so that we’ve got this great variety as we’re working our way through each of these seasons.

OAW: Having grown up in Seattle and now working all over the place and living in Colorado, does coming back to Bend feel like coming home?

Mitchell: Oh, 100 percent, totally. And it’s not just because I grew up in Seattle. I spent all my summers in Oregon. My mom is from Roseburg. By the time I was growing up, my grandparents had moved about an hour down I-5 to Grants Pass. So Grants Pass is where I used to spend my summers. I mean, if you were to look at my knees today, the vast majority of those scars I got in Grants Pass, falling off dirt bikes.

So I have been coming to Oregon my whole life. My mom’s entire side of the family is from Oregon. It was one of the things that I told the search committee, that it would be wonderful to feel like I’m back home for some time every summer. When I was a kid, my grandparents and I came over to Bend once, in the mid ‘80s. We came into Bend and I was like, “wow, this makes Grants Pass look like the big city.” And then I didn’t go back to Bend until 2021, when I auditioned. And I was like, “what happened?” Now it’s the big metropolis in Central Oregon. So it’s nice to have that lifelong perspective of what Bend was, which I remember so clearly from being a kid, and to see it now and to spend a good portion of my summer every year there.

Yes, it more than feels like coming home. It’s very special to me.

OAW: Our standard last question–what would you ask Brett Mitchell?

Mitchell: Oh my God. You know, very seldom do I get asked a question I’ve never been asked before. I guess I would ask myself, “where do you see the art form going?” The art form has changed a lot even in the course of my career. I’ve been doing this almost 30 years, and I got my doctoral degree 20 years ago, which means that was when I “finished” my training–we’re always training. When I was going to grad school, there was no such thing as, “what if we did the score for Empire Strikes Back live while we showed the movie?” It literally didn’t exist. The technology didn’t exist. They couldn’t have done that back then, even if they had wanted to. I was in academia, so it probably would have been looked down upon anyway. I’m glad to hear that that’s kind of going away, that looking down the nose kind of thing.

What does it look like 30 years from now? I mean, 30 years from now, I’ll be 75, almost 76, just wrapping it up-ish, hopefully. And what does it look like? I mean, I think that the more we can kind of hew to Duke Ellington’s “there are only two kinds of music,” the more successful we will be. I think if we say “dead white European males from the 19th century and everyone else need not apply,” that’s when the field gets in real trouble. Because I have conducted, I believe, over a thousand concerts now in my life. And at those thousands of concerts that I have performed for tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of people, never once have I seen a dead white European male, ever. Never happened. I’m not saying that they don’t have things to say to us, because they do, and they’re universal messages. But they shouldn’t be heard at the expense of people who have things to say today.

And the more we can successfully look at music as a continuum. Classical music is not a thing that happened. It’s a thing that is happening. It is a genre all its own, and a genre that is doing its level best, I do believe, to break down barriers, to break down walls, both in terms of who’s on stage and who’s in the audience and whose music we’re performing. So I think that the future of music is very bright for organizations that embrace the reality of who we are and when we are and where we are. We are not a museum. We are not there to encase works and to put them on a pedestal and to look at them and say, “oh golly, isn’t that lovely?”

That’s not what composers are trying to do. Composers are trying to communicate with immediacy. This is part of the challenge of doing something like Beethoven 5. Imagine how paradigm-shattering and mind-blowing it would have been to hear that piece for the first time. And yet that piece is now over 200 years old, and we’ve all heard it many times. So how do you recapture that immediacy? Beethoven wants to grab you. So how do we grab the audience?

The thing about music that’s really well known is it loses its power. It loses its impact. And I’ll give you two perfect examples from the world of film. The first is the shower scene from Psycho. The second is anytime you hear the shark theme from Jaws. Back in 1960, when Psycho came out and Janet Leigh was getting hacked to death in the shower, and Bernard Herrmann has those screeching strings–that must have been truly terrifying in the theater. If you think about Jaws and those two notes, how terrifying. I mean, John Williams won the Oscar for that score. And I have done Psycho in performance, and I have done Jaws in performance. And you get to those scenes, and people laugh. Not because it’s funny, but because it’s like, “oh, right, there’s the wee, wee, wee,” or “there’s the doom, doom, doom, doom, doom.” So it loses its power.

Mitchell: Beethoven 5 loses its power with overexposure. This is why we try not to repeat ourselves too much, so that when the time does come for immediacy, it can really land.

I think the ability to take an audience on a journey that really is a clear conversation, so that the way you hear the first piece impacts the way you hear the second piece and the way you heard those first two pieces impacts the way you heard you hear the third piece. We have all sorts of visual possibilities now. I don’t see anything wrong with incorporating visual elements in concerts. We have eyes as well as ears, and there’s nothing wrong with trying to engage more than one sense at a time.

I think the organizations that are the nimblest, that are willing to zig and zag, rather than, “we are an ocean liner, we are classical music, this is the direction we are headed.” It’s like, “yes, but it’s an iceberg, don’t you see the iceberg?” You’ve got to be able to, you know, take the schooner this way.

So what do concerts look like in 30 years? Gosh, I don’t know. Immersive, I think. I think all of the senses will be engaged somehow.

I don’t believe for one second–maybe eight years ago, I would have believed this–but after COVID, I don’t believe for one second that people are only going to stay at home and listen to music. I have seen it myself. As we all got back into the concert hall, people wanted to be in the hall. People needed to be in the hall. People need the communal experience. And particularly today, where we’ve got so many blips and bings and pings and alerts and dings–for all of us to come together, shut up, shut off the devices, and let the composer or composers take us on the journey that they’re trying to take us on.